Methodical software development - what must be considered when a small project suddenly becomes large

Not all software development projects are necessarily large, at least not at the beginning. But what happens when a small project, built by 1-2 developers and a designer at a moderate pace, suddenly gets a large budget, and the scope of work increases significantly? Is it enough to multiply the number of team members by 3 or 5?

Over time, we have learned many lessons, and although everything worked out well in the end, the parties' time and energy waste were higher than they could have been. This post talks about potential stumbling blocks based on our experience.

How does a project usually start, and what is an MVP?

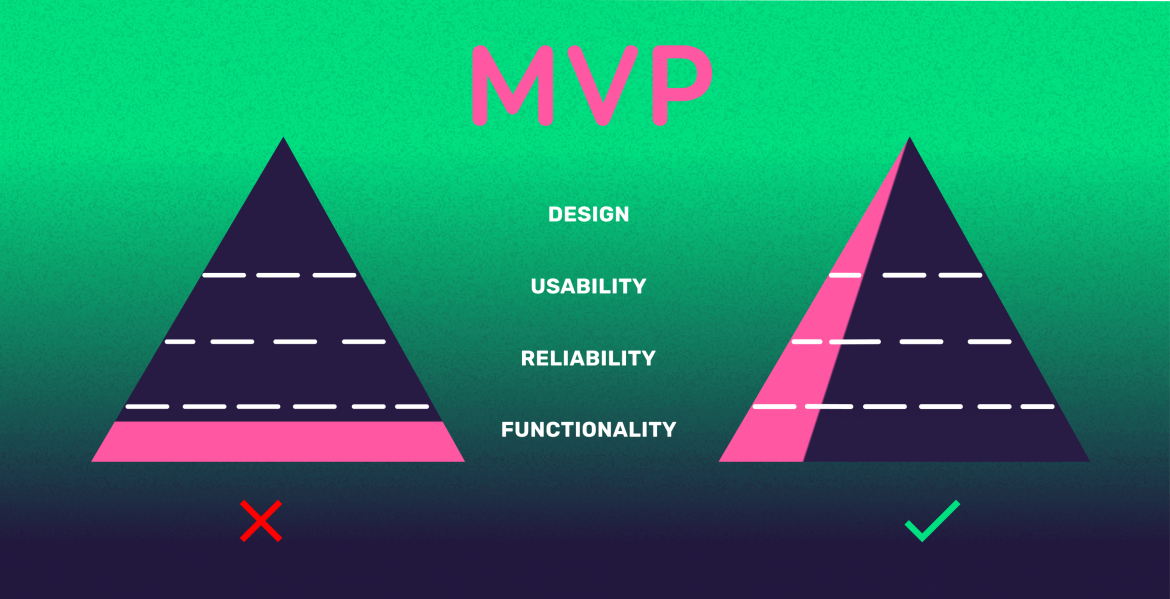

The customer turns to us to create an MVP (minimum viable product) with the terms of reference. MVP or the minimum working solution (product, service) is the first version of the system that is ready to be used.

With the help of MVP, we can assess whether the idea is solid and whether the end users like the solution. To create an MVP, we put together a small agile team consisting of two developers and usually one designer, plus quite often a tester. The last two roles might not be full-time.

The customer manages the pilot project and describes the functionalities (user requirements). An application is put together in this process that focuses on end-user functionality.

Typically, in the name of reduced short-term workload, less time is devoted to the convenient operation of all administrative functions and the sustainability and scalability of architectural solutions.

The goal is speed and efficiency, and the first version is usually ready within months with a limited budget. Such a pilot project will also help build trust and is a foundation to further good cooperation with the customer.

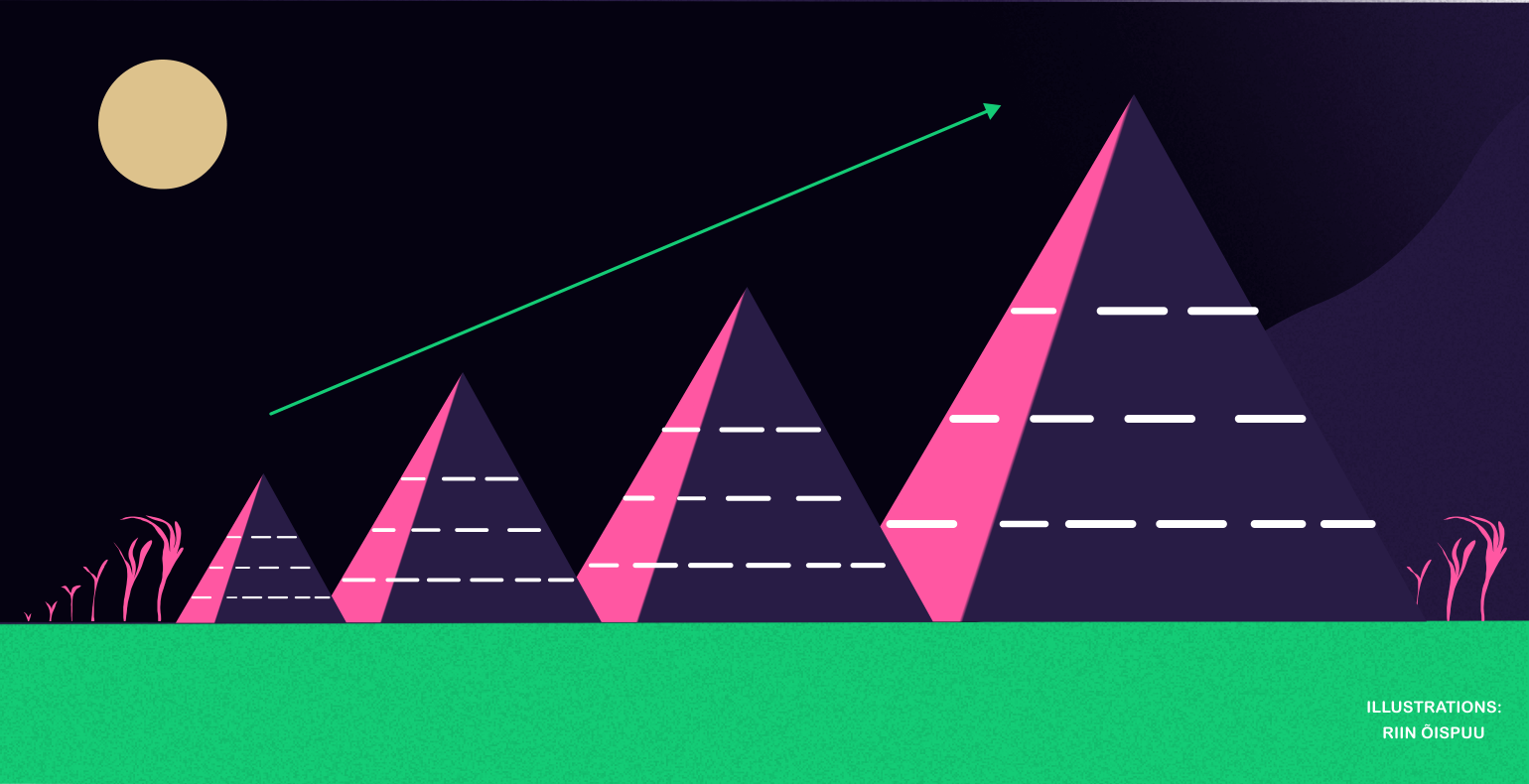

What happens to an MVP, and how does a small project grow into a big one?

There are two directions beyond the MVP:

- the solution will gradually be improved with the same or even smaller team. Typically, this happens for niche services where and more significant investments are not economically viable or in cases where the service needs to be further developed to assess its potential success and/or find funding. All this can take years to complete, and there usually will not arise any significant problems in established cooperation with the customer.

- the product or service is part of a larger (world conquest) plan. MVP proved to be successful, and the customer has the funding (it does not matter much where the money comes from: own funds, investors, or a grant) to quickly start implementing a system based on MVP, but with significantly expanded functionality. Both the client and us are looking forward to the new phase of the project - the hope is to build a prominent, exciting, economically prosperous, and/or high-impact solution. Unfortunately, this is where the most considerable risk of problems arises in cooperation.

To prevent problems, it is necessary to a) analyze the suitability of the technical platform of the existing solution and, if necessary, make changes, and b) assemble a qualified team or teams that will methodologically develop the new system and have all the necessary roles. Let us look at them in turn.

Suitability of architectural solutions and technical debt

When creating an MVP, technical (architectural) choices are made based on the fastest and most efficient way to complete the application quickly. However, these options may not be scalable or sustainable enough for a large team to develop on.

Also, creating an MVP often generates a significant amount of technical debt in the name of short-term development speed. This is perfectly acceptable, as the MVP aims to show that the idea is usable and works.

Architectural choices in the language of metaphors: the technical solutions for building a garage do not have to be as powerful as building a multi-story building; it would be a waste of money. However, if the need to add an apartment building on top of the garage becomes apparent later, it makes sense to analyze whether the construction choices are still suitable or need to be revised.

Starting with a much larger development, we need to take a step back and reassess the application architecture.

In doing so, the following should be considered: a) whether there are technical details that should be fixed immediately, reducing the technical debt to an acceptable level, and b) whether the technical architecture created is scalable, sustainable, and maintainable enough, given the new mission. If not, it must be rebuilt (refactored) before proceeding with developing functionalities.

Honestly about refactoring: in agile development, it is common for the existing technical solution to be refactored extensively during development. Why? Because "doing it perfect the first time" may not be possible (needs change over time) or is more expensive and time-consuming.

The problem is that an application that is difficult to develop technologically can look and work great on the outside. If we now go to the customer with the news that no new functionalities will come next month, as the team is working on refactoring and liquidating the technical debt, disputes can quickly arise.

One solution is to do this in parallel with implementing new functionalities if the system's status allows it. However, it is essential to ensure that this is the case; otherwise, you may later have no choice but to rewrite the application from scratch for technical reasons.

Although tempting for developers, we recommend avoiding it at all costs - we have seen many cases where the market share of an application was permanently lost during the from-scratch construction of a new system.

What to keep in mind when making architectural choices? They must be appropriate to the situation. If it is known that the planned lifecycle of the system is 10+ years and there is no huge hurry, you could look at more modern technological solutions, such as microservices + micro front-end.

Conversely, if there is a lot of time pressure, you could choose proven scalable solutions. The more innovative the solution, the more time and work it takes in the beginning. The bonus, however, is (hopefully) better future development and maintenance speed.

Why is it essential to apply a systematic development methodology to a large project?

Software development is a human creation. More functionality requires a larger team to complete it in a reasonable amount of time. However, it is necessary to understand and manage the connections and dependencies between the various parts of this functionality, which requires time and experience.

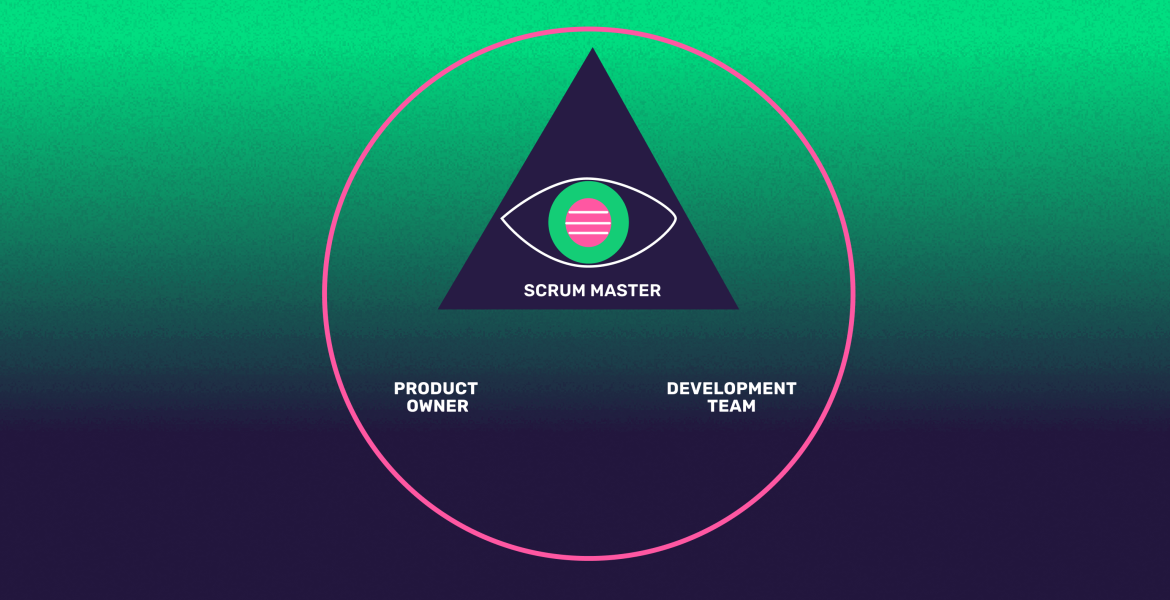

With the addition of people and functionality, the complexity of creating a system increases exponentially. Once a team has grown to 5 or more people, it is vital to implement a methodical software development process (usually Scrum) to ensure information flows in the team and that team members do not have to wait for one after the other.

It is also crucial that the team has the capabilities to carry out all aspects of the development process. If the customer attempts to run the whole project and describe the requirements in sufficient detail for development, keep in mind that it is a full-time (or more) job and requires strong software development and analysis competence. Role conflicts also come into play.

The reality is that the three roles for Scrum (Product Owner, Scrum Master, and Team Member) in the development of larger systems are somewhat oversimplified - specialization is required. It is important to involve the tester(s) and systems analysts in the project.

Developers are never as good testers as specialized testers. Systems analysts can assemble the big picture, break it down into logical parts, describe details and dependencies, and thus partner with the customer in defining, evaluating, and ranking the functionality.

In our experience, it is also problematic for the customer to take on the role of both product owner and project manager (Scrum Master). Scrum Master must have good software development management competence and sufficient time to perform all methodological activities.

On the one hand, he/she should be removing obstacles and making sure the team works sustainably, including explaining to the product owner their expectations cannot be met within the desired budget and time.

Being in two roles simultaneously risks putting too much pressure on the team, making it relatively easy to get the opposite result, as motivation is lost and the team breaks down.

In summary, we generally recommend to customers in larger projects:

- form a team with all the necessary roles and specializations (including UX / UI designer, architect, systems analyst, tester, developers, project manager)

- implement a systematic software development methodology

- take on the role of product owner, who is responsible for describing needs in general terms and setting priorities. The product owner team is formed with the input of the systems analyst and architect, who then describes it in the form required by the rest of the team.

Productivity and deadlines

As we mentioned, software development is a human creation, where the complexity of adding people and functionality increases rapidly because the work is not infinitely divisible to be carried out in parallel.

This results in the following rule: 5 times more working hours (budget) does not mean 5 times more functionality, as part of the budget is spent managing the added complexity of business logic and interpersonal communication.

The bigger the team and the shorter the deadline, the more extra money it takes. By trying to get the same functionality ready faster, there is no point in increasing the team size beyond a certain limit, as it has no positive net effect. Also, do not forget Brooks' rule: Adding human resources to a late software project makes it later.

Also, one team cannot be too big: we recommend that an ideal development team is 7, in some cases 9 people. If there is too much functionality for one team to build in the desired time, multiple teams must build the application simultaneously. This is doable; it is simply a matter of accepting that efficiency (i.e., how many units of functionality you get for one unit of money) will decrease as the complexity increases again.

Brooks rule in metaphorical language: sounds familiar? Guests come and try a variety of dishes in the kitchen. Someone is constantly in front of you; you cannot get anything from the drawer. You are in a hurry and getting annoyed, but the cooking is not progressing any faster.

At one point, you will politely ask the helpers to enjoy the wine, and you can prepare the meal alone pretty quickly. So it is in software development: at one point, there are too many cooks in the kitchen who will inevitably not be able to deliver everything there effectively.

Now let us talk a bit about deadlines. It is essential to understand that no deadline is 100% certain: each deadline is always accompanied by a probability of being completed by that time. The more certainty we want, the larger the buffer planned to deal with unforeseen circumstances. Wishing 100% certainty would be result infinity.

Which probability should one choose? When there are many dependencies, and the effects of delays are large (for example, just-in-time production), it pays to be more conservative. However, this has a price - when creating systems with several developing parties, the total development speed decreases and it must also be ensured that there are no gaps in the team's work, even if tasks were completed earlier.

In general, it is most sensible to discuss this between the parties, for example: is it enough to set a goal that by the end of 80% of the development iterations, all the planned things have been done?

Deadline rule: if the project falls behind schedule, it is usually impossible to make up the gap. If the project starts going well, at best, it will be possible to keep the gap at the same level. Exception: The project was not a high priority for the client or the service provider but is now a priority for both with an increased budget.

If the deadline is shortened, it must be accompanied by actual changes in the way the work is done (by the way, emphasizing to the team that this deadline is critical is not a change). Otherwise, we only changed the probability of completion by the agreed time, not the actual completion time.

The mistake usually made is setting too aggressive deadlines (with a low probability of completion), which may look good on paper, but in reality, frustrate both the team and the client.